Beekeeping learning and honey crop 2019

Having started beekeeping with a “nucleus” colony of Buckfast bees in June 2017 this year has been about building the number of colonies, learning properly about swarm control and queen rearing. Its been a bonus to get some semi respectable harvests of honey too!

In this blog I will review the year, explaining in some detail how I have increased the number of hives, the different honey harvests and the fun I have had catching swarms. I also touch upon how keeping honey bees is not really the best way to help pollinators in general and when “farmed” conventionally. Sadly it is like much of modern farming in that it is working against nature. Importantly I also list links to much more informed sources of bee keeping knowledge from which I have learnt a lot.

Two very different honeys - summer blossom and late summer heather

Getting bees through the winter can be a fraught time. Lack of sufficient stores for them to utilise to keep their cluster warm, dampness and fluctuations in temperature are the biggest dangers. Through the winter months when temperatures are too low to forage (and of course when reliable supplies of nectar and pollen are very scare anyway) the bees need to reply on their 40lb or so of essential honey and pollen stores that they have conserved from the previous year. Fluctuations in temperature are an issue as early warmth can encourage the queen to go into spring laying mode too quickly, The presence of eggs and young larvae simply means that the internal temperature of the brood nest needs to be increased further, up to a surprisingly high 35°C.

This year we had record breaking February temperatures so the development of colonies started early. Luckily for us as temperatures did dip the bees managed fine and we came out of the winter with a 100% survival rate. So four hives in total - our original colony with two walk away splits and a combined hive made from two swarms I caught in 2018 - all started the year in various levels of strength and health.

21 March 2019 - our four successfuly over wintered hives with a poly hive ready for first split of the year

Just to explain a walk away split is a very basic way of increasing your number of hives. The technique involoves removing into a new hive (it often goes to start with into a small nucleus hive or poly hive) as a minimum a frame of eggs and young larvae and a frame of stores along with some young nurse bees. Left alone (the walk away part) the bees will recognise they have no queen and using a young larvae will feed additional royal jelly to create an enlarged queen cell. All being well 16 days from the date the egg was first laid a new virgin queen will emerge. After a number of days the young queen will need to leave the hive on one or more mating flights which if successful gives her the ammunition to lay eggs for the rest of her life. This could be up to 3 or even more years although bee keeppers seem to be increasingly reporting queen issues whereby life spans and mysterious disappearances of queens is becoming more common. Some of the literature suggests that walk away splits are a poor method of queen rearing. However, my experience so far as been positive and most have succesfully lead to a new queen and new colony.

A 2018 Queen bee in March 2019

So back to the Spring build up. Three of my hives were expanding rapdily with the queens laying plenty of eggs and the bees foraging on the warmer days bringing back loads of pollen. This is very obvious as large blobs of fascinatingly coloured pollen attached to the “pollen basket” on the hind legs of the bees. Its a great sign too as it indicates that the hive has viable eggs and larvae which need this protein food for their development.

The fourth hive, however, was struggling. Although a queen was present there were very few bees and very few eggs. They also seemed to be suffering from nosema. This is a fungal disease with the fungus attaching the bees digestive cells one sign being spotting outside the hive. This is effectively the result of dysentery as bees leave the hive. As a precaution I removed this hive to an isolation site - my step daughters garden. I didn’t want to worry her so thought it prudent not to tell her their problem! Without much hope for their survival I left them with plenty of sugar syrup to give them some help now that the weather in late March was back to cold and wet.

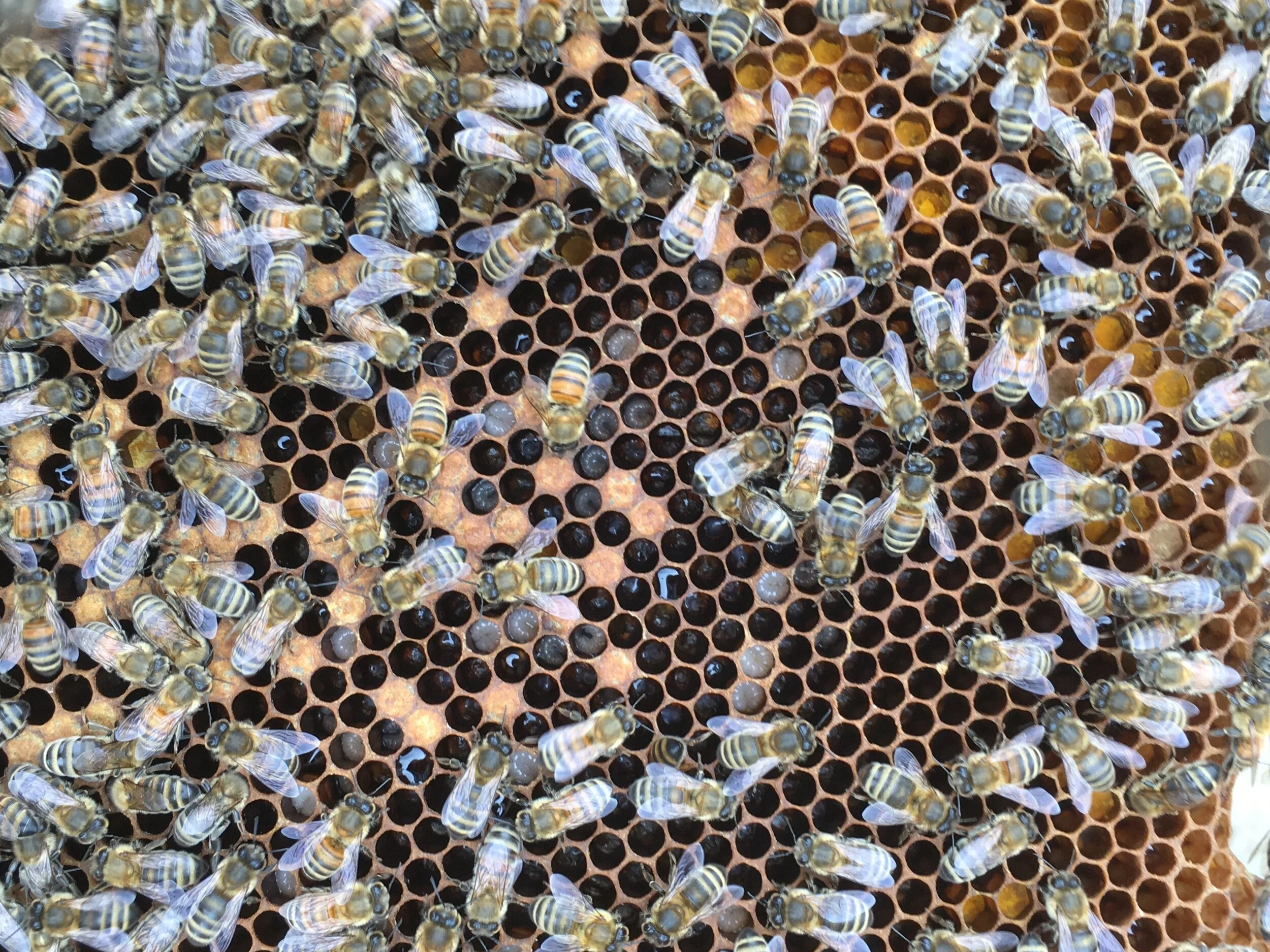

A frame of bees building up well wpot the eggs, larvae and pollen stores

Despite the problems with hive 4 the other three were expanding rapidly and on the 26 April I was forced to carry out a walk away split on hive 2. We were leaving for a weeks holiday and I was worried that unless I reduced numbers in the hive that they may swarm. This would mean I would return from holiday having lost a good proportion of these bees and hence any chance of a Spring honey crop. Probably over cautious and I could have given them more space by putting on a honey super. This is an extra box that is added to the hive above a queen excluder. It gives extra space for the foragers to deposit nectar which will be transformed into honey by the action of the bees fanning to reduce the water content. The queen excluder is important as it prevents the queen accessing this space and spoiling the honey stores by laying eggs in and amongst!

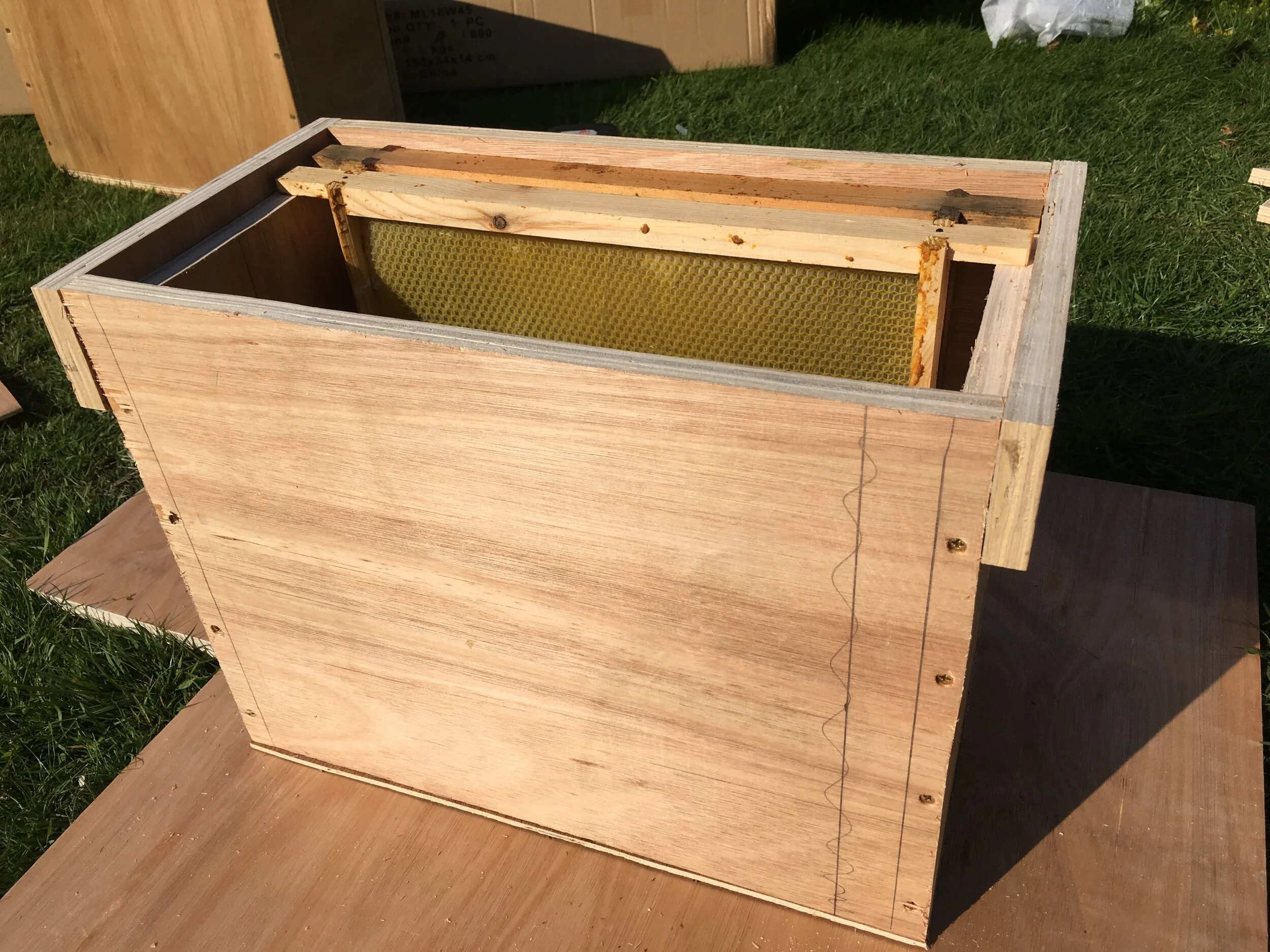

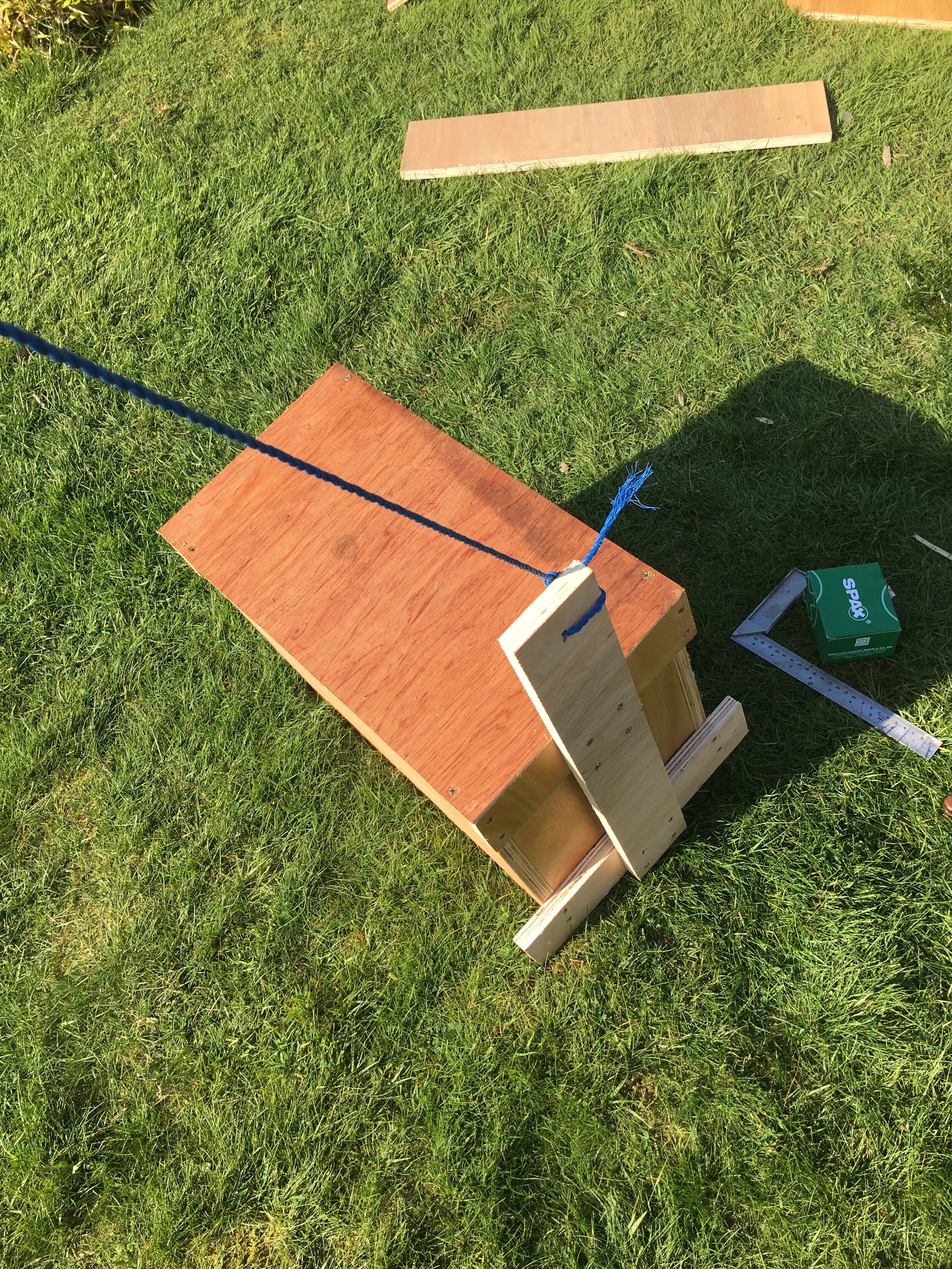

With the bees developing well thoughts turned to how I would manage the bees for the rest of the year. Concious that swarm control is an important part of beekeeping not least becausce recklessly losing a swarm can create problems for others, I built a bait box. Swarming is the natural method by which honeybees reproduce. The existing queen leaving with a good proportion of the hives foragers and drones to set up a new home leaving an embryonic queen ready to emerge in her queen cell. The swarm looks for a suitable new home and if this happens to be someones chimney or within a roof space it can create an expensive removal job. Having bait boxes gives the bees a safe alternative although arguably a bait box within your own apiary/garden is too close to your existing hives. More likely you will catch someone elses bees. I gleaned this and a wealth of fasinating infomration about how bees behave in nature from the work of Professor Seeley from Cornell University. His 2019 book, The Lives of Honeybees sets out lessons from how wild honey bees act in nature to help manage them better in captivity.

I designed my bait box to hold 6 frames and equipping it with a used frame for the scent I placed it 15 feet up in a native hawthorn tree. With the entrance facing south and of the dimensions specified by Professor Seeley to mimic what bees look for in the wild I spent the next few months carefully examining the entrance for activity every time I passed close by.

Bees starting to ibiuld natural comb after being given a “top bar” seeded with a line oif wax

By the end of April I had added honey supers to the three progressing colonies ready for an increased flow of nectar in May. Reading more about natural beekeeping I placed a few simple wooden bars with a small line of wax melted along their length amongst the commercial frames of wax foundation. It was amazing to see the bees building their own wax comb from these. it was also interesting to note that the cell size they built was different to that of commercially made foundation depending on whether they were intending it for normal worker cells, drone brood (larger) or honey storage (which also appeared larger).

Starting them young - examinging the start of honey being deposited into a super frame

For about three weeks in May there was what beekeepers refer to as a nectar flow. I estimated that on the best days each hive made almost a frames worth of honey - I later weighed the best frames and found they can weigh up to 2kg - predominantly the weight of honey. With 11 frames in a super this would be a maximum of 22kg in a box. By the end of May it was apparent that the nectar flow had ended and it was quite clear that we were experiencing a “June Gap”. Apparently this abrupt end of any avaialable nectar from spring flowers before summer flowers are ready does not happen quite as obviously each year. However, this year I found that the bees did not store any excess honey until July and probably consumed most of the honey they had stoed within the brood box. However, with some honey made in the supers during May we were able to take our first crop and extract the honey using our spinning extractor.

In May and June I carried out a couple of experiments in swarm control with a view to simultaneously increase the number of hives. They were what is known as a Vertical Split and a Demaree. The knowledge was gained form the excellent resources from the Apiarist and the links explain the process for those interested far better than I can. These both worked to an extent although on balance the Demaree technique I found easier to manage. It was also ultimately more successful as I produced a new viable hive from a queen cell formed in the upper box and I did not have to move boxes around as much as with the vertical split. You Youtube videos below show how these worked in practice.

The swarm season started late for me given how much press both locally and nationally was indicating that it was a prime swarming year. However, on 16th July a large cluster of bees appeared in our large oak tree the same site that had yielded a swarm the previous year. After a few failed attempts at shaking them off into a waiting box below I finally managed to house them in a spare box by sawing the branch off! A little precarious as this needed doing from the top of a ladder. I am fairly certain that this swarm was from one of my own hives. I had been monitoring hive 3 which had built up to a large size and I had seen queen cells developing. I had not taken any preventative action as I thought these may have been supersedure cells rather than swarm cells. Supersedure cells are developed by the bees when they wish to replace an existing queen either as her egg laying performance is deteriorating or because she as died/gone missing. In these instances it is better to let the bees look after the process themselves. However, checking the hive after finding the swarm it was apparent from the numbers of bees that many had left. So they were looking to naturally swarm taking the old queen and leaving the queen cells to allow the existing hive to naturally reproduce.

Swarm in the old oak tree

The 16th of July must have been a key swarming day as late that evening I happened to spot a further swarm this time conveniently placed in a low gorse bush. This was simple to catch by placing an empty hive box underneath and shaking the bees in. This time there was no evidence that the bees were from my hives so possibly in coming from elsewhere. There is a potential risk that swarms from unknown sources may contain disease and the best advice is to quarantine in an isolation apiary until any potential disease is ruled out.

More conveniently placed swarm in a low gorse bush

The summer nectar flow occurred in July and at my home apiary was predominantly confined to three weeks. Although short it did yield some more honey of really fine flavour with a lovely almost sharp floral after taste. This we concluded was mainly blackberry blossom as its main source.

With the main flowering season over there was an opportunity to take a couple of hives west towards the later flowering heather on the moors. A friends garden provided an ideal location and after shutting the bees in one night we moved the hives into place early the next morning.

Moving a couple of hives to the heather moors

During August and into September these two hives did yield some heather honey, despite reports that the heather beetle was diminishing the heathers potency.. This was much darker than our blossom honey and as it is thixotropic we needed to press this out rather than use our extractor. However, the flavour was well worth the effort!

Beautiful naturally built honey comb filled with nearly ripe honey. This has not been capped over with wax by the bees indicating that water content is probably still a little high.

All in all I am pleased with the bee keeping year. At the end of the season we have 12 hives so the potential to harvest more honey next year. This will depend on how well we have prepared the bees to come through the winter, their level of stores and the control of potential disease, particularly the varroa mite.

Next year I will explore further the subject of natural bee keeping as a possible future management strategy. This would be much more in keeping with the work of Professor Seeley and could ultimately more away fro the need for chemical treatments.

Some beekeeping resources

Associations

The Sheffield Beekeepers Association - the beginners course offered is a great way to start beekeeping with confidence.

British Beekeepers Association - produces the monthly BBKA newsletter and has a useful facebook page.

Beebase - the National Bee Unit has a wealth of information on bee health and treatment for diseases. All beekeepers should be registered with Beebase.

Online Bee Keeping Mentors

Stewart’s Beekeeping Basics - fabulous resource with videos and additional helo for Patrons

Richard Noel - entertaining Youtube videos from his apiaries in France.

The Apiarist - excellent practical advice, blogs and discussion

Podcasts

The Barefoot Beekeeper - Phil Chandler advocates a balanced approach to beekeeping, using top bar hives and minimising intervention. His podcasts are readiyl available and the web site fasinating.

BBC - Costing the Earth - Verity Sharp wants to keep bees but will her hive actually reduce the insect diversity of her corner of the British countryside?

Treatment Free Beekping - An American Podcast with Solomon Parker who talks to people all over the world dedicated to treatment free beekeeping.